Dissecting Harriet Cole: Uncovering Women's History in the Archives

by Alaina McNaughton

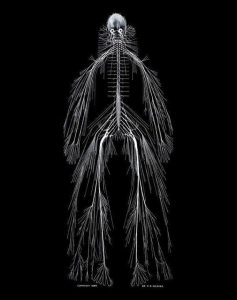

The complete nervous system dissection known as “Harriet.”

NOTE: Some of the information in this 2018 blog post is incorrect and does not reflect our current understanding and the documentation available. The way we understand history is shaped by what we know, what others knew, what has been shared or published, and the time we live in. For more information, visit our Historical Human Remains page. (Updated August 2022)

Reflecting on recent events like the Women’s Marches and #MeToo Movement, the Society of American Archivists (SAA) selected Perspectives on Women’s Archives, edited by Tanya Zanish-Belcher and Anke Voss, for its 2018 One Book, One Profession reading initiative. The purpose of this SAA initiative is to bring professionals together to discuss trends in archival practice. In this case, collecting and raising women’s voices in the archives. Recently, I participated in the Delaware Valley Archivists Group’s Fall Meeting at the Chester County Historical Society. At the meeting, we used Perspectives on Women’s Archives as a springboard to discuss women’s collections, women’s archives, and women’s voices in archives. During the discussion, someone brought up the difficulty of finding working-class or impoverished women of color in archives. I immediately thought of Harriet.

If you haven’t been following along with our social media series #WhoisHarriet, here’s a quick synopsis:

Each Tuesday for the past 10 weeks, I’ve posted a #WhoisHarriet post on our social media accounts (Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram). These posts feature a transparent look at our most popular archives mystery, Harriet. Harriet is a complete dissection of the cerebrospinal nervous system, dissected and mounted in 1888 by anatomist Dr. Rufus Weaver of Hahnemann Medical College. I used this series to uncover and document any concrete information about the living Harriet. Articles on Dr. Weaver and his 1888 dissection suggest that Harriet Cole was an African American woman who worked at Hahnemann as a “scrubwoman” or “janitor.” The same articles also suggest that, upon her death, she would donate her body to Dr. Weaver. There is however no proof that she donated her body to Dr. Weaver, no proof that she worked at Hahnemann, and no proof that her name is even Harriet Cole. For the #WhoisHarriet series, I attempted to use our collections and outside sources to find proof of her donation, proof that she worked at Hahnemann, and proof that her name was in fact Harriet.

If Weaver’s dissection is in fact a working class African American woman named Harriet Cole, what are the chances her name appears in the archival record? If she isn’t there, how can I still tell her story?

Finding Harriet in the Archival Record

In our archives, we collect copies of publications written about Dr. Rufus Weaver and Harriet; each tells the same story with newer articles simply regurgitating older articles.

Some stories are more elaborate than others, but each boils down to the same points. Harriet Cole was a 35-40 year old African American scrubwoman who worked for Dr. Rufus Weaver at Hahnemann Medical College. She died of tuberculosis in 1888. Before her death, she willed her body to Dr. Weaver, because she knew he needed cadavers for his anatomical preparations.

My goal for this research project and social media series was to prove/disprove this story by uncovering concrete evidence using our collection and additional outside sources. I have laid out my research process and accompanying photos below. Follow my process of looking for Harriet.

Questions to Answer:

- Did a “Harriet Cole” exist during this time period?

- Did a “Harriet Cole” donate her body to Dr. Rufus Weaver in 1888?

- Did a “Harriet Cole” work for Dr. Weaver or Hahnemann Medical College at any point between 1869-1888? Did Hahnemann Medical College keep a list of employees during the 1870s-1880s?

Harriet Cole: She Exists, But...

It is entirely possible that a woman named Harriet Cole existed in 1888 in Philadelphia.

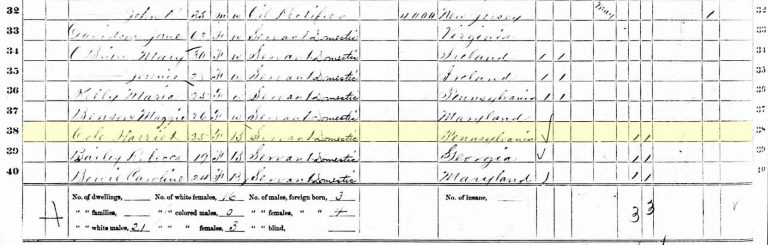

After searches on Ancestry and FamilySearch, I found an 1870 census record for a black woman named Harriet Cole who worked as a domestic. This Harriet lived in Philadelphia’s Ward 9 in 1870, the same ward as Hahnemann Medical College at the time. I also found a death certificate from March 1888 for a Harriet Cole who died of tuberculosis with the “place of burial” listed as Hahnemann Medical College right around the time Weaver acquired the cadaver. These two instances of a “Harriet Cole” in the historical record could almost certainly be the woman I am looking for, but this is circumstantial evidence. There could be other Harriet Coles who did not participate in the census.

So I can’t know for sure.

1870 Ward 27 Census with a Harriet Cole highlighted.

Body Donation: Understanding Time and Place

It is entirely possible that Harriet Cole donated her body to Dr. Rufus Weaver.

When Weaver acquired the cadaver in 1888, the United States was just closing the door on grave-robbing and other less than savory methods of body procurement. That being said, 1888 was still an era when body donations were not documented as rigorously, which makes sense as to why we don’t have any definitive evidence. It was also an era when most Americans disapproved of dissection and voluntary body donations were quite rare. Many states legislated that unclaimed bodies of people who died in hospitals, asylums, and prisons would be allocated to state medical schools for the purpose of anatomical dissection. This alleviated the need for body snatching, but it marked body donation as a sign of poverty. Harriet Cole was probably poor and wished to donate her body to Weaver rather than leave any family member with burial costs. We don’t have any paperwork outlining the donation of her body to Hahnemann or Dr. Weaver.

So I can’t know for sure.

Hahnemann Medical College Staff Records: Slim to None

It is entirely possible that a Harriet Cole worked for Hahnemann Medical College sometime between 1866-1888.

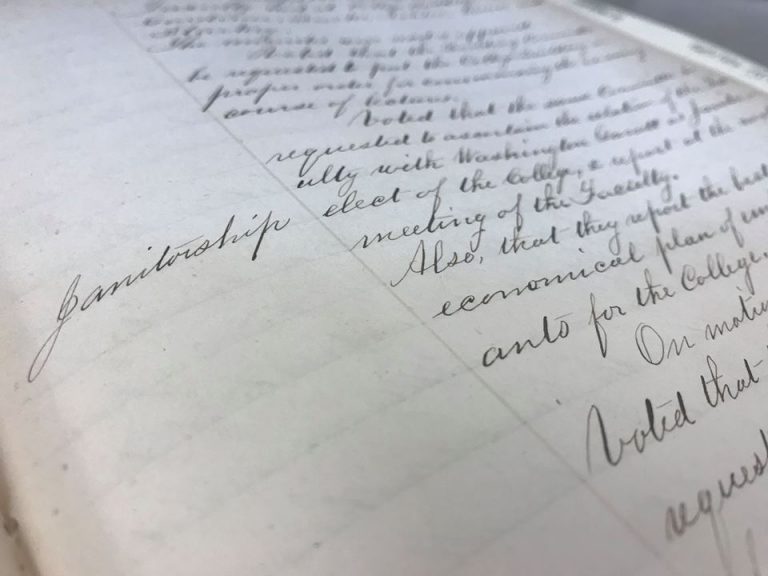

Hahnemann Medical College Board kept records of their meetings between 1866-1888. The Board records however didn’t track nitty gritty information like school or hospital employment, but rather financial information for each academic year. For instance, in the minutes from the 1883-1884 academic year, they wrote, “janitor’s wages to Apr. 1, 84...845.00” There is however no mention of a janitor’s name.

In the Hahnemann Medical College Faculty minutes, there was more detailed information about staff. I came across records of janitors, including their names, in the Hahnemann Medical College Faculty Minutes from 1850-1869. Medical school janitors were often African American men appointed by the faculty. These positions typically lasted for one year and during that time the janitor and his family lived at the College. These janitors were tasked with procuring bodies for the medical student dissections. It is possible that Harriet came to Hahnemann as the wife/family of a janitor. However, there is a gap in the faculty minutes between 1869 to 1900, so I can’t determine if Hahnemann appointed a janitor by the name of “Cole.”

Harriet could have been a casual employee of Dr. Weaver, but Weaver’s personal records and papers have never been found (if they even exist at all).

So I can’t know for sure.

A page from the Hahnemann Medical College Faculty Minutes discussing janitor positions.

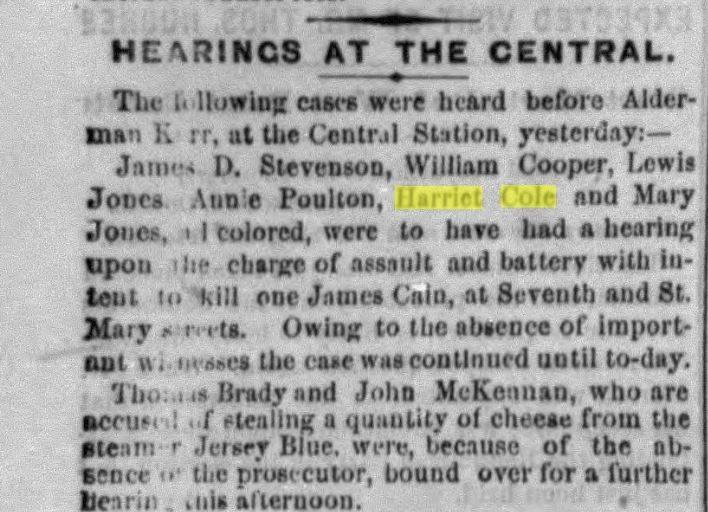

Bad Press is Better Than No Press

Hitting a research wall, I remembered the Ulrich adage “well-behaved women seldom make history.” Turning to the Philadelphia Inquirer, I got some hits for “Harriet Cole.” On Friday October 7, 1870 (and the next 2 subsequent weeks), under “Hearings at the Central,” I found a case involving a “Harriet Cole.” Cole was involved in an attempted robbery and physical assault. This Harriet Cole fits the age, race, and time frame of our Harriet, but there is no conclusive evidence.

This could be the same Harriet Cole, but I can’t know for sure.

“Hearings at Central” section of the Philadelphia Inquirer from 1870. Harriet Cole’s name is highlighted.

Telling Harriet’s Story

“We are grappling with the challenges of unearthing heretofore unknown women and coming to grips with how and why the “smallness” of their work or their worlds illuminates dimensions of the past we urgently need to understand.”

This passage from Antoinette Burton’s “Finding Women in the Archives” exemplifies my attempt to uncover Harriet. While it may seem like too much time and energy spent on the “smallness” of her world, it is incredibly necessary and important to uncover. What was her relationship actually like with Dr. Weaver? What did she think about donating her body to Weaver? Did she actually sign away her body to him? Could she read and write? Did she know what she was doing? These are the “dimensions of the past” that we urgently need to understand. Learning more about Harriet would bring out the story of a working class black woman, someone traditionally marginalized in the archives and historical record. It would also highlight the history of race and class in body donations and anatomical dissections in Philadelphia in the 1880s-90s, a relatively unknown subject.

Weaver’s achievement permeates the current historical narrative, leaving Harriet a mythologized fragment of his triumphant tale. It puts Harriet in a role desired for her--a kind-hearted black woman who jumped at the chance to donate her body to Dr. Weaver. By sharing our lack of archival evidence, we are exposing the harm of the traditional story-- Harriet as merely a plot point not a person. Instead of perpetuating this, we can now emphasize her absence from the record and use this as a discussion or lesson on why she’s not there. Archives have a duty to collect and raise women’s voices in the archives, whether it be sharing, digitizing, creating educational material, or finding and rectifying absences or silences in the collections--and this is one just one example. While it may be challenging work, this work will illuminate the worlds of unknown women, giving us a more accurate and richer look at the past.

For further information, please check out our series #WhoisHarriet.

Sources:

Antoinette Burton. “Finding Women in the Archive: Introduction.” Journal of Women’s History, Vol. 20 No 1, 149-150. 2008.

Raphael Hulkower. “From Sacrilege to Privilege: The Tale of Body Procurement for Anatomical Dissection in the United States.” The Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2011. p. 23-26