Birth Control, Sex Education, and Eugenic Feminism: The Peculiar Activism of Women Physicians

by Sebastian Porreca, Archives Intern

Birth control, family planning, and sexual education have had significant impacts on sexual health and how people think about sex across the globe. Each of these public health subjects have a long and storied past in the United States, but the culminating moment in all of these histories was the push to publicize them in the early 20th century. Many of us can not imagine a time without the prominent, albeit sometimes controversial, features of women’s health and public health such as family planning and sex education. The so called “social hygiene movement” began gaining steam around 1910, placing an emphasis on ending prostitution, advocating for contraception to decrease unwanted pregnancies, and focusing on preventive medicine. Leading the way in the social hygiene movement were a number of prominent women physicians, such as Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and Margaret Sanger, who pushed for the representation of women in medicine, and presented a new emphasis on health issues regarding women. The prevalence of women in the social hygiene movement stemmed from long standing, patriarchal gender roles that positioned women as caregivers, nurturers, and child bearers, who, by extension, felt the need to project these instincts onto society as a whole and morally nurture society. It is a case by case basis whether these women, who were in many senses far more progressive than these gender roles, actually believed and coalesced to these expectations, or utilized them to further the causes of professional women, and there is evidence that can be presented for both. Either way, the programs many of these women pushed were far more progressive than their time. They sought to erase the stigma around sexual urges, teach sex education to young women, and decrease deaths caused by clandestine abortions and unplanned pregnancies. However, there was a dark side to the progressive pushes made by these feminist physicians.

A major current in the social hygiene movement was the concept of eugenic feminism, which asserted that women were the bearers of the next generation of the “race” and therefore had the legal right to vote and politically advocate for interests concerning them, their children, and the “race” as a whole. A clear example of this ideology is a speech given by Dr. Margaret Clark in May, 1915, later to be reprinted in the Woman’s Medical Journal in June, 1915. The speech/essay basically asserts that women physicians are an elevated group of “mothers’ helpers” who turn to medicine out of their natural and God given maternal instincts. With this innate caregiver ability, women physicians, in Dr. Clark’s thinking, are a natural progression of motherhood that allows them to advise and assist new mothers, care for and morally develop children, and deal with the “ignorance” and irrationality of new mothers and women patients that men don’t have the patience to deal with. Women physicians who perform outside of these caregiver roles are downplayed. Furthermore, due to this projection of the caregiving and morally superior nature of women onto society as a whole, Dr. Clark asserts that “a new day has come for the motherhood of the race.”

It would be both unfair and false to claim that every woman or woman physician involved in projects regarding social hygiene or suffrage were believers of eugenic feminism. Nonetheless it is important to recognize how the eugenics movement influenced the ideas of women social hygienists. A significant example of this is the issue of birth control, a large aspect of the social hygiene movement. The push for birth control, led by Margaret Sanger, sought to combat the various problems caused by unintended pregnancies and unintentionally large families. These problems included not only health issues and deaths caused by the strain of multiple pregnancies or an illegal abortion, but also the financial strain and lack of necessary resources for impoverished families to raise these unintended children. These are often arguments used today in favor of birth control and family planning, and were by all means very progressive for the early 20th century, but many birth control advocates also heavily relied on eugenics to support their position.

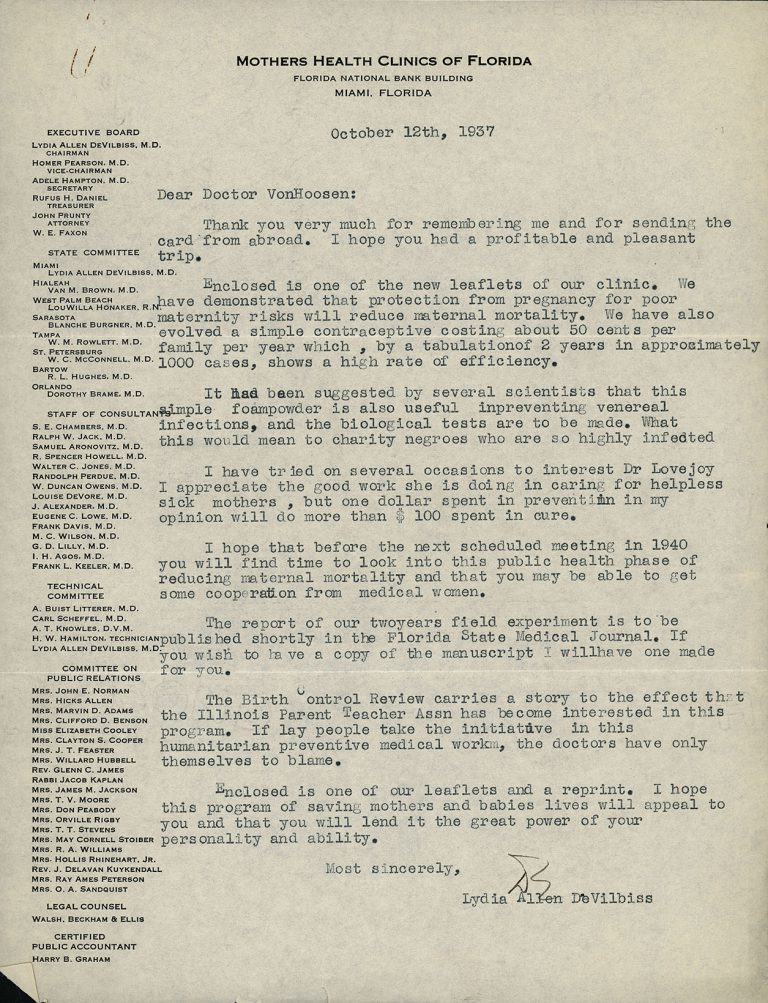

The prominent social hygienisist Dr. Lydia Allen DeVilbiss perhaps exemplifies this position best. On one hand, Dr. Dee (as she was known) was a huge proponent of affordable, accessible birth control, and even opened the first long running birth control clinic in New York City, working closely in New York with Margaret Sanger. In a letter to Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen dated October 12, 1937, Dr. DeVilbiss describes how she went on to develop affordable contraceptives “costing about 50 cents per family per year which… shows a high rate of efficiency.” However, despite her actions in the field of birth control, her intentions and ideology around these actions were ultimately hinged on eugenics and concepts of racial purity.

The Letter Dr. Lydia Allen DeVilbiss wrote to Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen in 1937 detailing her work in preventive medicine and birth control. (Letter from Dr. Lydia Allen DeVilbiss to Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen. 12 October, 1937. The Bertha Van Hoosen Papers. Box 1, Folder 2. Drexel College of Medicine Legacy Center.)

In a chapter of her 1923 work titled Birth Control: What is It? Dr. DeVilbiss explains quite frankly that the aim of accessible, legal, and affordable birth control is not necessarily to help the plight of impoverished, marginalized communities. Rather, it is intended to make sure that they can utilize birth control and therefore procreate less. In her reasoning, if birth control is illegal or expensive, only the rich and powerful could access it, which would mean that the birth rate of the “better stock” would decrease. By her extension, then the “poor, ignorant, insufficient, and the dullards” would be able to procreate freely, surpass the “better stock” in birth rate, and overall taint the “American race.” If this isn’t shocking enough, Dr. DeVilbiss was also a huge proponent of forced sterilization, with hundreds of patients “of low intelligence” being sterilized against their will at her Mother's Health Clinic in Dade County, Florida.

Medical Women's Journal in which she was interviewed. (Medical Women's Journal. vol. 51 no. 10, October 1944. Drexel College of Medicine Legacy Center.)

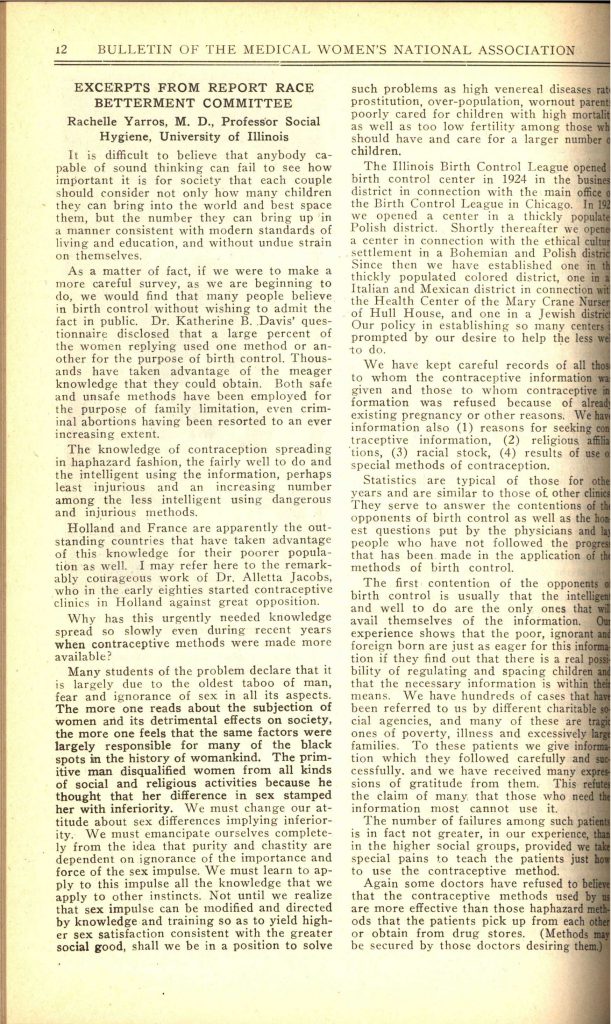

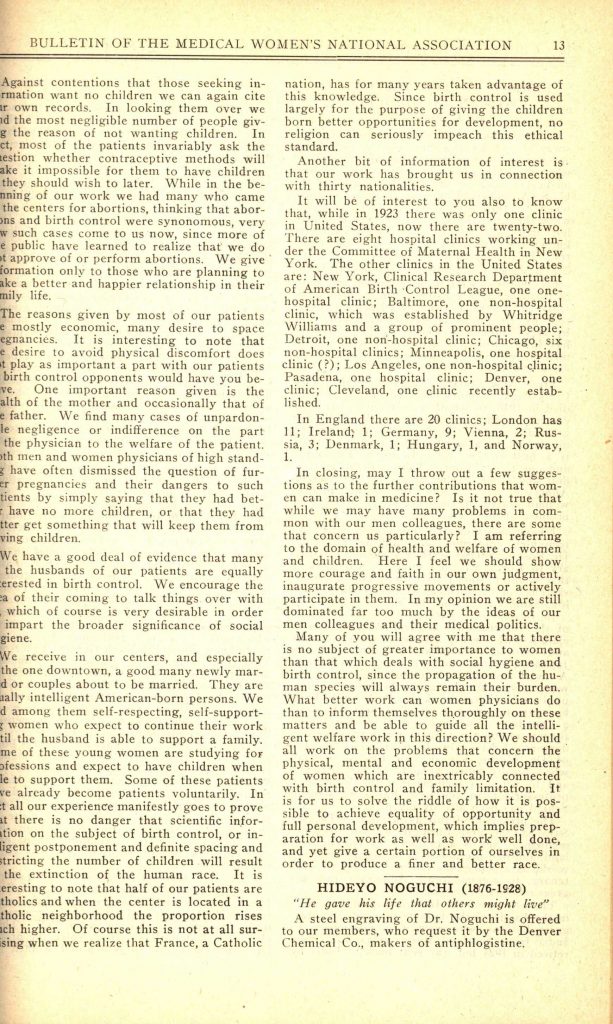

Certainly not all women were as adamant and frank on their views of eugenics as Dr. DeVilbiss. Many women physicians were genuinely concerned with issues affecting impoverished, marginalized communities, and made great strides to aid communities with these public health issues. However the language and ideas used by physicians like Dr. DeVilbiss made their way into most mainstream discussions of social hygiene at the time, even if these discussions were not focused on eugenics or racism. For example, the October 1928 report from the Medical Women’s National Associate (MWNA) Committee on Race Betterment, despite the less than desirable name, presented some really progressive and ahead of their time opinions on sex and gender. The author of the report, Dr. Rachelle Yarros, links the subjugation of women, and patriarchal structures with the vast stigma surrounding sex and sexuality, and pushes that sex education and birth control are a necessary path to break this stigma. Dr. Yarros’ report also details birth control clinics opened in poor immigrant neighborhoods, but, unlike Dr. DeVilbiss, Dr. Yarros showed a genuine care and desire to help impoverished immigrants. Still, this eugenics-esq language often seeps into her report, most obviously in the fact that the committee she is reporting from is called the Committee on Race Betterment, but also in her decision to use “racial stock” as a factor in her data gathering.

The report from MWNA's Race Betterment Committee written by Dr. Rachelle Yarros in 1928. (Yarros, Rachelle, M.D.. "Excerpts from Report Race Betterment Committee"." Quarterly Bulletin of the Medical Women's National Association. No.22, 12-13, October 1928.)

This example serves to show how pervasive the language of eugenics and racialism was in the social hygiene movement, even if the activism of women like Dr. Yarros were not necessarily focused on sterilization, racial culling, or eugenics. This is a little uncomfortable for those looking today at the social hygiene movement, but it serves as an important lesson in understanding the public health services that continue to benefit so many. Unfortunately, the language and terminology included in many writings on social hygiene from the 1910s through the 1930s borrowed from and used the then popular science of eugenics. This was not because all social hygienists or advocates of women’s health were firm believers in eugenics and racial purity, but rather many simply deployed the lexicon they knew and what they were taught. With that in mind, we should not negatively judge every woman who used this terminology that, by today's standards, is socially unacceptable and demeaning. We can not discount these women simply by the language that they used, but rather we need to closely analyze the actual actions and programs they implemented for the sake of their perceived “good” and observe the actual ideology behind these programs. This does not in any sense justify the horrific outcomes of eugenics or justify those who supported eugenics and racial cleansing, but it gives us a context in which to view the women who participated in the social hygiene movement and ultimately made it possible to have access to contraception, birth control, and sex education. In understanding the whole picture of how we got these innovations in women's health and public health, it is important to not just observe the good, positive aspects, but also acknowledge and understand the darker side of these innovations. This allows us to truly and honestly observe how social movements function and learn from our past in order to make social movements and medical advocacy more ethical and inclusive for all.

Special thank you to Elliott Earle! The sources and notes they gathered on eugenics/social hygiene were a huge help to me in writing this, and I am very thankful for their help!

Sources:

Allen DeVilbiss, Lydia, M.D.. “Increase In Populations” Birth Control: What is it?” Ch. 5. 67-73. (Small, Maynard and Company, 1923).

Cecily, Devereux. “Woman Suffrage, Eugenics, and Eugenic Feminism in Canada” Women's Suffrage and Beyond. 1 October, 2013.

Clark, Margaret Vapuel, M.D.. “Medical Women’s Contribution to the Education of Mothers.” Women’s Medical Journal, 25:6 (June 1915) 126-128. (Presentation, 18th Annual Meeting, Women’s Medical Society of Iowa, Waterloo, Iowa, May 1915.)

Letter from Dr. Lydia Allen DeVilbiss to Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen. 12 October, 1937. The Bertha Van Hoosen Papers. Box 1, Folder 2. Drexel College of Medicine Legacy Center.

Safford, Pearl interviewing Allen DeVilbiss, Lydia, M.D.. “An Interview” Medical Woman’s Journal, vol. 51, no. 10, (October 1944) 29-34.

Yarros, Rachelle, M.D.. “Excerpts from Report Race Betterment Committee” Quarterly Bulletin of the Medical Women’s National Association. No. 22, 12-13 (October, 1928).